Inuit in Labrador

Inuit in Labrador

By Brenda Clarke

Winter 1981

1st Reprint: Winter 1985

2nd Reprint: Fall 1991

[Originally published in printed form]

The Labrador Eskimos, or Inuit¹ as they call themselves, are the direct descendants of the Thule Inuit, an Alaskan people who migrated into Canada and Greenland about 1000 years ago. Archaeologists believe that the Thule people first arrived on the Labrador coast around 1400 A.D., coming southward from Baffin Island.

Upon their arrival in Labrador, the Inuit may have encountered the Dorset Eskimos who had been living on the Labrador coast for over 2000 years. The Dorset people, called Tunnit in the traditional stories of the Inuit, were not related to the newcomers. The two groups had very different tools and house structures although they hunted the same animals. Archaeologists are not sure what happened to the Dorset people in Labrador or elsewhere in the Canadian arctic.

During the early period in Labrador, 1400 to 1700 A.D., the Inuit population expanded as far south as Hamilton Inlet. Although they had no permanent settlements south of Hamilton Inlet, we know that the Inuit sometimes journeyed to the Strait of Belle Isle to trade, hunt and even to raid the camps of European fishermen, including the 16th century Basque whaling stations. At this time the Inuit had some contact with European explorers and whaling ships along the northern coast but this contact did not affect their way of life to the extent that it did in later times.

During the early period in Labrador, 1400 to 1700 A.D., the Inuit population expanded as far south as Hamilton Inlet. Although they had no permanent settlements south of Hamilton Inlet, we know that the Inuit sometimes journeyed to the Strait of Belle Isle to trade, hunt and even to raid the camps of European fishermen, including the 16th century Basque whaling stations. At this time the Inuit had some contact with European explorers and whaling ships along the northern coast but this contact did not affect their way of life to the extent that it did in later times.

The Inuit travelled a great deal during the year seeking animals which were their sources of food, clothing, light, warmth and tools. Summer travel was either overland, on foot, or on the water using skin boats. The kayak was an enclosed, skin-covered boat which carried only one person. The larger umiak, an open skin-covered boat, could carry about 20 people. For winter transportation, a komatik, a large sled pulled by a dog team, was used. Dogs were an extremely important part of the economy. The Inuit depended on them not only for transportation, but also for help in the hunt and as an emergency food supply.

The sea provided many animals for the Inuit hunter. Seals, walrus, whales, cod, char and salmon were taken at different times of the year. Caribou, the only important land animals, were mainly hunted late in the summer. Birds, lake trout and berries were other sources of food.

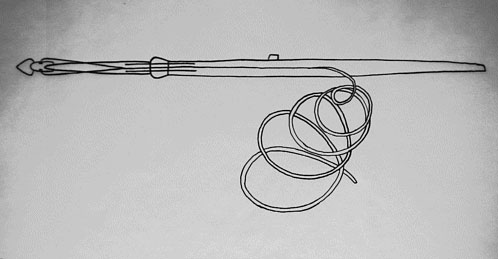

A harpoon was used to hunt the sea mammals - whales, seals and walrus. This weapon consists of a blade of bone, stone, or in later times, iron, a harpoon head and foreshaft of ivory or antler, a long shaft and a sturdy line. Men hunted these animals by kayak during open-water weather and on foot in the winter and spring. When hunting larger seals and walrus in open water, an inflated seal bladder float was used to help drag the harpoon line as the animal attempted to escape. Large whaling harpoons were employed in the hunting of whales. Several hunters cooperated in the hunt and the umiak was used for their transportation in this dangerous pursuit.

A harpoon was used to hunt the sea mammals - whales, seals and walrus. This weapon consists of a blade of bone, stone, or in later times, iron, a harpoon head and foreshaft of ivory or antler, a long shaft and a sturdy line. Men hunted these animals by kayak during open-water weather and on foot in the winter and spring. When hunting larger seals and walrus in open water, an inflated seal bladder float was used to help drag the harpoon line as the animal attempted to escape. Large whaling harpoons were employed in the hunting of whales. Several hunters cooperated in the hunt and the umiak was used for their transportation in this dangerous pursuit.

Hunters also worked together on the late summer caribou hunt in the interior. Once the herd was located, several people, usually women and children, drove the animals into a lake or river. The caribou were then hunted from kayaks using pointed lances or with bow and arrow. A great deal of ingenuity was involved in the caribou hunt. Because of the large numbers of animals killed, it was important that the slaughter be convenient to the desired butchering and catching place. Therefore, the hunters drove the animals as near to the place as possible before killing them. In this way, the "meat" provided its own transportation!

The remains of Inuit fish weirs are often found at narrow channels in rivers and streams. The weirs are constructed of large, heavy stones piled together forming a trap for the fish, which will mill around a barrier rather than turning back. They were taken with a fish spear, constructed of a long shaft with a sharp point and two side prongs which had small barbs attached at right angles. When the spear penetrated the fish, the side prongs, held with sinew, flexed away from the point. Once the fish was firmly on the end of the spear, the side prongs closed together and the barbs helped prevent the fish from slipping off. With the aid of the weir and the fish spear, the Inuit family could take several hundred fish in a single day. These would be dried and cached for human and dog food the coming winter.

In addition to these and other hunting tools, the Inuit had a wide range of domestic utensils, including lamps and rectangular pots made of soapstone, the ulu or circular-bladed woman's knife, mattocks for digging and snow beaters for beating loose snow from clothing; these last two were often made from whale bone. One of the most ingenious devices was the bow-drill, used for boring holes in umiak and kayak frames and in such tools and weapons as harpoon heads, endblades, toggles for dog harnesses and needles.

The Labrador Inuit had three types of dwellings. During the summer, they lived in conical skin tents. Large rocks weighted down the edges of skins. Hundreds of stone tent rings, left by the Inuit after the skin covering was removed, dot the northern landscape. Snow houses were used as temporary dwellings on winter hunting trips. The more substantial semi-permanent winter houses of stone and sod were dug into the ground for added warmth. The entranceway was excavated approximately 20 cm lower again than the living area, forming a "cold trap"². The Labrador Inuit exhibit at the Newfoundland Museum shows a reconstruction of such a dwelling. It is a small, single family house dating from 1400-1700 A.D. The foundation was lined with large rock slabs and a framework was erected to support a skin lining and a sod roof. This framework was usually made of wooden poles if spruce was available; elsewhere whalebones, as shown in the Museum diorama, may have been used as rafters to support the roof. These houses were very snug and warm. Light and heat were obtained by burning seal oil in flat, crescent shaped soapstone lamps. With the addition of a rectangular soapstone pot suspended above it, the lamp was a woman's prized possession; she took pride in keeping it filled and trimmed during her lifetime, and after death it was placed in her grave, with a hole neatly drilled through it to allow its "spirit" to join her in the afterlife.

Labrador Inuit clothing consisted of a hooded coat, trousers (either knee or ankle length), knee high boots and mittens. Men's and women's styles varied slightly. Sealskin boots were worn all year round. In the summer the skins were dressed³ but in winter the hair was left on. Winter clothing was usually made of caribou or seal skin. Two layers of clothing were worn during the winter. The first was turned hair side in to form pockets of air which provided both insulation and protection from dampness caused by perspiration. With the addition of a second layer of clothing fur side out, the Inuit winter dress was proof against the coldest weather. The beautiful designs on Inuit clothing were achieved by insetting strips in contrasting colours from various parts of the animal's body.

The clothing on exhibit in the Newfoundland Museum has been reconstructed to the style current around 1750 A.D. Unfortunately, no original clothing exists in any museum collection from this period or from earlier periods. The reconstruction was made possible by researching the written and pictorial records left by the Moravian missionaries and early travellers.

The life of the Inuit in Labrador during these early times reflects a strong relationship between the people and their physical environment. They depended on sea mammals and caribou for all their sustenance and worldly goods and thus required skill and suitable weather conditions on land and sea to hunt these animals successfully. Between 1700 and 1850 there were many changes in Inuit life because of their extensive contact with Europeans. Trading posts and the Moravian missions appeared along the Labrador coast making it possible for the Inuit to acquire wooden boats, firearms and iron implements as well as European foods such as tea, flour and sugar, thus reducing their dependence on their environment.

The life of the Inuit in Labrador during these early times reflects a strong relationship between the people and their physical environment. They depended on sea mammals and caribou for all their sustenance and worldly goods and thus required skill and suitable weather conditions on land and sea to hunt these animals successfully. Between 1700 and 1850 there were many changes in Inuit life because of their extensive contact with Europeans. Trading posts and the Moravian missions appeared along the Labrador coast making it possible for the Inuit to acquire wooden boats, firearms and iron implements as well as European foods such as tea, flour and sugar, thus reducing their dependence on their environment.

Since the mid 19th century most of the old way of life has vanished. Firearms have changed the methods of hunting; harpoons were laid aside. Fur-trapping and trading with the Europeans became an important source of income and wage-earning jobs replaced their subsistence economy. Christianity, first brought to the Labrador Inuit by the Moravian missionaries, replaced the old beliefs. The tools, skin clothing and house styles common in the early period disappeared after the mid 1800s in favour of European settlers. The Newfoundland Museum has created an exhibit that reflects a part of the Inuit lifestyle of the early period between 1400 A.D. and 1700 A.D. before many of these changes occurred.

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING:

Hawkes, E.W. The Labrador Eskimo. Anthropological Series, Geological Survey, Ottawa, Memoir 91, No. 14, 1916. Reprinted in 1970 by the Johnson Reprint Corp.

Taylor J. Garth. Labrador Eskimo Settlement of the Early Contact Period. National Museums of Canada, Publications in Ethnology No. 9, 1974.

Them Days [magazine]. Happy Valley, Labrador.

Tuck, James A. Newfoundland and Labrador Prehistory.National Museum of Man, Ottawa, 1976.

Turner, Lucien M. Indians and Eskimos in the Quebec/Labrador Peninsula. Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of Ethnology, Report No. 11, Washington, 1894. Reprinted in 1979 by Presses Comeditex, National Library of Canada, Bibliothèque nationale du Québec.

FOOTNOTES:

1. "Inuit" means people and is pronounced ee-new-eet. It is the term in the modern Inuit language - Inukitut - that Eskimo in Canada use to describe themselves. Singular is "Inuk."

2. "Cold Trap". This helped to keep the cold drafts in the entrance tunnel from drifting into the main room. When it struck the rise, or step, the cold air tended to circulate back out the tunnel. The "cold trap" entranceway was a significant advance in Arctic house design and gave the Thule and later Inuit a much greater [degree] of comfort than would have been known to the Dorset Eskimo.

3. "Dressed Skins". This refers to the practice of scraping the hair off the hide before tanning. The Inuit used dressed skins mainly for making waterproof boots and mittens, and covers for kayaks and umiaks.