Early Photography in Newfoundland

Early Photography in Newfoundland

By Antonia McGrath

Winter, 1980. Reprinted Fall, 1991.

[Originally published in printed form]

There is a phenomenon surrounding the survival of most historical documents that goes beyond the limits of the medium. The photograph as a document is in a particularly precarious situation because the information contained in a photographic image is altered if we try to transfer it to any other medium; moreover, the photographic medium is in itself unstable. If unused fixer is not washed completely from the print or negative it will eventually cause deterioration; so, the means we have used to make the image permanent create an unstable situation for the material which supports that image. Without written information, the identity and age of a photograph may be obscured, and by our innocent mishandling of the material we often destroy the records which give photographs their relevance. The lack of public institutions to collect and provide adequate storage space and care has led to collections of glass plate negatives being stripped of their emulsions so that the glass my be re-used. The use of Elsie Holloway's glass negatives to build a greenhouse is not without precedent.

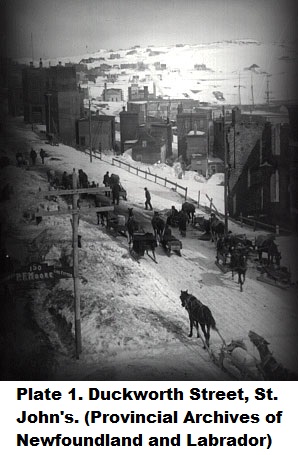

In St. John's and Harbour Grace, the photographs suffered the additional insult of fire, and documents which survived the fire of 1892 in St. John's, where the majority of photo studios were located, are rare. It is fortuitous, then, that the Newfoundland Museum¹ should house a collection of about five-thousand glass plate negatives. They have survived the vagaries of time and present us with a view of Newfoundland that has not been betrayed by the history of the plates.

In St. John's and Harbour Grace, the photographs suffered the additional insult of fire, and documents which survived the fire of 1892 in St. John's, where the majority of photo studios were located, are rare. It is fortuitous, then, that the Newfoundland Museum¹ should house a collection of about five-thousand glass plate negatives. They have survived the vagaries of time and present us with a view of Newfoundland that has not been betrayed by the history of the plates.

The plates appear to have come from four main sources: the Parsons Studio of St. John's, R.O.E. Holloway and the Holloway Studio of St. John's, Rubin T. Parsons of Harbour Grace and the Moravian Mission in Labrador. There are many other significant contributions that chance has relegated to obscurity, or that accident has prevented from being represented in the collection. We will never know, for instance, the maker of the wet collodion plates,² the earliest in our collection. Though journals from the turn of the century would indicate that photographers Lyon and Vey did a prodigious amount of work, what became of the contents of their studios is not known.

In 1839 Louis Daguerre captured the attention of the world with the announcement of his invention of what came to be known as a "daguerreotype".³ Newspapers in Newfoundland were too involved with the usual political mayhem to take note, but on March 10th, 1843 the following advertisement appeared in the Public Ledger:

-----

NOTICE.

Daguerreotype!

MESSERS VALENTINE & DOANE beg leave to call the attention of the inhabitants of St. John's and its vicinity, to an Art which has attained great celebrity and popularity in almost every city of Europe and America.

They have completed an apartment fitted for the purposes of Daguerreotype Portraiture, and have made other improvements and arrangements, by means of which they are confident of producing pictures of exquisite beauty.

The truth and high finish of Portraits by the Daguerreotype process, and the rapidity with which they are accomplished, render the Art deserving of universal attention, independently of its great value as a means of obtaining accurate LIKENESSES, as a comparatively small expense.

The Daguerreotype Rooms, at the Golden Lion Inn, will be opened on MONDAY, at 10 o'Clock, and will remain open daily from 10 to 4 o'Clock. Persons unacquainted with the art, are respectfully invited to call at the Rooms, and examine Specimens.

Portraits taken in any state of the weather. March 10.

-----

Subsequent advertisements also pointed out that "Mr. V. will be happy to paint a few Portraits in Oil."

William Valentine was a well known portraitist from Halifax and was the first permanent daguerreotypist in the British North American Colonies. Thomas Coffin Doane eventually achieved an international reputation by obtaining an "accurate likeness" of such prestigious subjects as Lord Elgin and Joseph Howe. Although a reasonable representation of their work exists [see: Burant, 1977], none of it seems to have survived in Newfoundland.

Charles F. Tousaint established himself as a daguerreotypist amongst the Water Street merchants in 1850. During the next thirty years techniques and processes underwent many changes. New photographic studios emerged in Newfoundland; the firms of Adams, McKenney, Chisholm, Smith, Dicks and Page Wood exchanged partnerships frequently. Of these early photographers, only Adams left a legacy. In 1860, H.R.H. the Prince of Wales visited Newfoundland. In August of that year David Adams informed the public that he was "receiving names" for orders for a special memorial of the Prince's visit at the Book Stores and the Ambrotype Rooms until his departure for England on the "Connaught". The purpose of his visit to England was to arrange for the printing of a lithograph of "The Landing and Reception of His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales at St. John's Newfoundland on the 24th. July 1860", by Day & Son, London, from his own photograph of the event.

Charles F. Tousaint established himself as a daguerreotypist amongst the Water Street merchants in 1850. During the next thirty years techniques and processes underwent many changes. New photographic studios emerged in Newfoundland; the firms of Adams, McKenney, Chisholm, Smith, Dicks and Page Wood exchanged partnerships frequently. Of these early photographers, only Adams left a legacy. In 1860, H.R.H. the Prince of Wales visited Newfoundland. In August of that year David Adams informed the public that he was "receiving names" for orders for a special memorial of the Prince's visit at the Book Stores and the Ambrotype Rooms until his departure for England on the "Connaught". The purpose of his visit to England was to arrange for the printing of a lithograph of "The Landing and Reception of His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales at St. John's Newfoundland on the 24th. July 1860", by Day & Son, London, from his own photograph of the event.

According to a report of the Legislative Council on December 10th, 1860, Mr. Adams presented a copy of the lithograph to the Legislative Council. It was generally felt that Mr. Adams had exhibited much artistic talent in bringing the picture to such a successful completion. The Hon. J. Hogsett, however, did not concur. He felt that Adams had presented a ludicrous caricature of the auspicious event. It was pointed out that his Excellency the Governor looked as if he had been exhumed for the occasion and that the Volunteer Riflemen were grossly libelled.

In 1860, this reaction was understandable. The eye had not yet learned to accept the new perspective provided by the camera lens. In Europe, the debate went on for decades as to whether or not truth in art is photographic truth. Certainly the drawing by "our special artist" for the Illustrated News was more acceptable to the contemporary public as it presented a more complimentary view of the occasion and paid more attention to the manner in which the Governor and the Cavalry were supposed to appear. As one of Mr. Adams' defenders pointed out, there remained not one solitary memorial outside of the memories of the Prince's visit, until the appearance of Mr. Adams' picture. Ironically, the Prince's visit provided Mr. Adams with his solitary memorial as nothing else of his work has survived.

Adams later moved to Harbour Grace and eventually sold his business to a man named Squires who took as his partner a local businessman, S.H. Parsons. Probably the best known of Newfoundland photographers, Parsons' enchantment with photography began around 1854 when he was ten years old and the first "Daguerreotype Man" arrived in Harbour Grace. He wrote that his curiosity "was excited beyond measure" and that he "longed to understand the splendid gradations from one tone to another...the beauty and exactness of outline". When he established himself in the business around 1869, he had only a rudimentary understanding of photography but within two years he was able to produce better work than this country had seen before. He obtained international recognition of his work by exhibiting in Europe and had complimentary reviews in The Philadelphia Photographer and Wilson's Photographic Magazine. His studio on Water Street which was operated by his sons Charles and William until 1936, was a St. John's landmark until it was insensitively renovated after a fire in 1976.

At the same time that S.H. Parsons was gaining a professional reputation, a committed amateur, R.O.E. Holloway, was also receiving attention for his efforts. Holloway was the President of the Methodist College and, coincidentally, a chemistry teacher. Chemistry was a considerable asset to a photographer in the 1800's, as the various chemical solutions necessary for processing could not be obtained ready made, but had to be mixed by the photographer. Holloway suffered from tuberculosis, and as a means of providing himself with what was considered a healthy environment, he and his family spent many summers touring the Island. After his death in 1904, his book Through Newfoundland With a Camera was published by his family who had assisted him with the preparation. In 1908, his son, Burt, and his daughter, Elsie, opened a modern studio on the corner of Bates Hill and Henry Street. Enviable even by today's standards, it was built for use as a photographic studio, with adequate natural light and numerous well appointed work rooms. It burned down in 1975, having undergone a metamorphosis beyond revision. Burt was killed in the Great War but Elsie continued on her own until 1946, when she was well into her sixties. There is hardly a person in St. John's who grew up between the First and Second World War who does not remember Miss Holloway. Though most of the work produced by any commercial establishment is functional in nature, Elsie Holloway's approach to children's photography was innovative and sensitive. Her work is cherished by its owners.

At the same time that S.H. Parsons was gaining a professional reputation, a committed amateur, R.O.E. Holloway, was also receiving attention for his efforts. Holloway was the President of the Methodist College and, coincidentally, a chemistry teacher. Chemistry was a considerable asset to a photographer in the 1800's, as the various chemical solutions necessary for processing could not be obtained ready made, but had to be mixed by the photographer. Holloway suffered from tuberculosis, and as a means of providing himself with what was considered a healthy environment, he and his family spent many summers touring the Island. After his death in 1904, his book Through Newfoundland With a Camera was published by his family who had assisted him with the preparation. In 1908, his son, Burt, and his daughter, Elsie, opened a modern studio on the corner of Bates Hill and Henry Street. Enviable even by today's standards, it was built for use as a photographic studio, with adequate natural light and numerous well appointed work rooms. It burned down in 1975, having undergone a metamorphosis beyond revision. Burt was killed in the Great War but Elsie continued on her own until 1946, when she was well into her sixties. There is hardly a person in St. John's who grew up between the First and Second World War who does not remember Miss Holloway. Though most of the work produced by any commercial establishment is functional in nature, Elsie Holloway's approach to children's photography was innovative and sensitive. Her work is cherished by its owners.

Rubin Parsons, of Harbour Grace, was the son of S.H. Parsons' brother, Edward. Rubin was the eventual inheritor of the furniture business that his Uncle had forsaken for photography and, by all accounts, Rubin wished he could do the same. Photography was his first love and he regarded customers in his store as a necessary evil, since he longed to be in his darkroom. His photographic documentation of the early transatlantic flights was much published in The New York Times and other international newspapers.

The photographs we have surrounding the four Moravian missionary families in Labrador contain a wealth of information. Naive in execution, they are a delight to the eye. They were taken as snapshots by the missionaries themselves. Snapshots provide us with an insight that is sometimes not evident in more studied forms of photography. For reason of composition or intent, a photographer may reduce the amount of background detail and follow a more formulated approach to image making. As a medium, we are all familiar with the snapshot; the images are universal. The intimacy of a snapshot serves to draw us more sharply into the past.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Burant, Jim. Pre-Confederation Photography in Halifax, Nova Scotia. The Journal of Canadian Art History Vol. IV, No. 1 (Spring 1977): pp. 25-44

Greenhill, Ralph, and Andrew Birrell. Canadian Photography 1839-1920. Coach House Press, Toronto, 1979.

Holloway, R.E. Through Newfoundland With a Camera.Sach & Co., London, 1905.

Newhall, Beaumont. The History of Photography from 1839 to

the Present Day. Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1964.

Philadelphia Photographer Feb. 1987: pp. 68-70; March 3, 1888: pp. 134-136.

Scharf, Aaron. Art and Photography. Penguin Books Harmondsworth Ltd., 1968

Wilson's Photographic Magazine April 5, 1980: pp. 196-199.

FOOTNOTES

1. This collection of glass plates now resides in the Provincial Archives of Newfoundand and Labrador.

2. The Wet Collodion process was introduced by Frederick Scott Archer in 1851 and was used until the Dry Plate or Gelatin Emulsion process was perfected in the 1870's.

3. The discovery of photography is attributed to Joseph Nieephore Niepce who succeeded in fixing an image of the view from his window at Gras in 1826. Niepce formed a partnership with Louis Jacques Mande Daguerre, but the former died four years before Daguerre produced his first successful daguerreotype. On August 19, 1839, at the Institut de France in Paris, the distinguished physicist, Francois Arago, announced to the world on behalf of the French Government the details of Daguerre's process which became known as the daguerreotype. Like Ambrotypes and tin types, the Daguerreotype process produced a positive image, but it is from a negative-positive process developed by an Englishman, William Fox Talbot that our modern photographic processes stem.