Entering the Great War

On the evening of August 4, 1914, Walter Davidson, the Governor of Newfoundland, received a cable informing him that Britain was at war. As a colony, Newfoundland and Labrador officially entered the war when Britain did. However, the exact role the colony would play was still to be determined.

Davidson reacted quickly. On August 8, he wired London to say that Newfoundland and Labrador would raise five hundred men for land service and one thousand men for

naval service. Prime Minister Patrick Morris supported this decision without calling the Legislature together.

On August 12, 1914, a public citizens' meeting in St. John's endorsed the actions taken by the Government and passed a resolution that led to the creation of the Newfoundland Patriotic Committee. (The committee was soon re-named the Patriotic Association of Newfoundland.) The committee assumed responsibility for recruiting, training, and equipping the Newfoundland Regiment during most of the war.

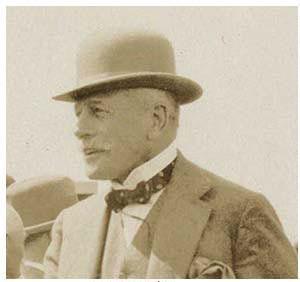

Governor Davidson and Prime Minister Morris

The Rooms Provincial Archives A37-18

Governor Davidson and Prime Minister Morris organized a meeting of prominent St. John's citizens which, in turn, unanimously passed resolutions calling on the Governor to appoint a public committee to supervise and control Newfoundland and Labrador's forthcoming part in the war.

The Rooms Provincial Archives A23-134

In effect, the Newfoundland Patriotic Committee, as it was first named (later to be called the Patriotic Association of Newfoundland), took on the responsibilities of government that in other countries was the work of Departments of Militia.

In creating the Newfoundland Patriotic Committee, the Morris administration hoped to remove partisan politics from the war effort, and thus improve its own public image. To do so, the administration first got Liberal, and then Unionist, support for the Association. Morris hoped that this broad, political unity would also divert public attention from the widespread economic issues that would certainly follow as a result of war.

Opposition parties also gave their support to the war effort. In a special session of the Legislature on September 2 to discuss the colony's contribution, the Leader of the Opposition, John Kent, stated:

"This is not a time when we should think of Party differences. This is a time when our land calls for united action!"

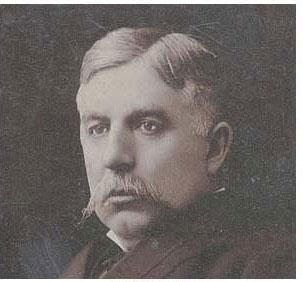

William Ford Coaker: Founder - Fishermen's Protective Union

The Rooms Provincial Archives VA83-66.1

Although Newfoundland's commitment to the war was widely supported, some individuals did question how much it would cost the colony. One of these people was William Coaker, politician and founder of the Fishermen's Protective Union (FPU). Coaker was also Editor of the Mail and Advocate, the official paper of the FPU and the only paper in the colony not dependent on government advertising for its survival.

In the August 14, 1914 edition of the Mail and Advocate, he wrote:

"Let England's hour of necessity come, and she will find in Newfoundland 20,000 of the primest warriors ever born, ready to do or die. That day is yet far off and the Colony's chief duty now is to put her house in order and arrange things so that in event of the hour of necessity arising Terra Nova's sons will be strong and healthy and prepared to meet the foe. Half starved men will be useless as fighters. Thousands through the failure of the fishery will have to fight starvation, an enemy fifty times more dreaded than the Germans on the field of battle or the seas."

Under pressure from the governing coalition, of which he was a part, Coaker eventually supported the war when, in 1917, he voted for a conscription (mandatory enlistment) bill. He even went so far as to actively recruit from the Fishermen's Protective Union. Sixty-nine young men, who became known as “Coaker's Recruits”, enlisted to represent not only Newfoundland but also the FPU. Ten of these recruits died in action or from wounds received in action.

At the end of the war, the issue of the cost of the war to the colony would be one that proved significant to its future. The Government of Newfoundland contributed over $15 million to the war effort. This amount grew to over $38 million by the 1930s when pensions and interest on war loans were included. The ultimate result was the colony's loss of independence in 1934.