The Setting

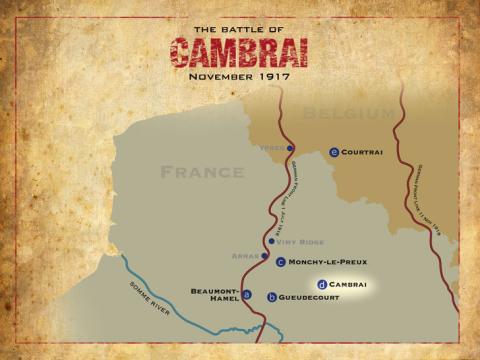

As the stalemate on the Western Front continued through the fall of 1917, the armies of both sides began to explore new military tactics. While the Germans began using mustard gas and small assault forces, the Allies worked on coordinated attacks involving infantry and tanks. The Battle of Cambrai was to be the Allies' "Great Experiment" using this approach.

Allied Tank

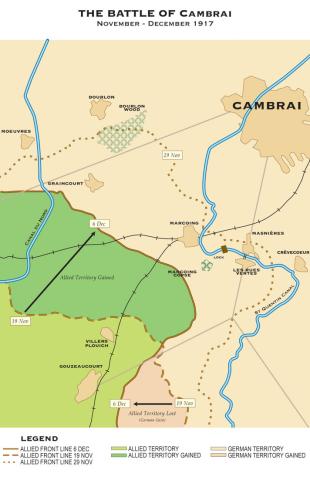

The Allied goal was to break through a ten kilometre section of the German Hindenburg Line in northeastern France. Their objective was the city of Cambrai, a vital German supply centre.

The Battle of Cambrai

November 1917

Cambrai, France

The Allies planned a surprise attack. As the landscape was favourable for the deployment of tanks, they would not have to use their customary artillery bombardment prior to the attack to destroy the enemy's barbed wire and other defences. The advance would involve 278 tanks and six infantry divisions — including the 29th Division.

The Plan

Prior to the start of the battle, members of the Newfoundland Regiment spent several weeks practicing how to advance with tanks. On November 20, they moved into position. The Regiment was to follow the main attack on the Hindenburg Line. Its objective was to seize the St. Quentin Canal and the town of Masnières, clearing the way for cavalry to move on to Cambrai.

Advancing with Tanks

Newfoundland Objective

The Action

November 20

At 0620 on November 20, the Allies began their advance on Cambrai. Waves of Allied tanks and infantry quickly overwhelmed the enemy at the Hindenburg Line. At 1010, the 29th Division began its advance. The men easily advanced to the Hindenburg Support Line. At this point they encountered enemy machine gun fire and suffered their first casualties.

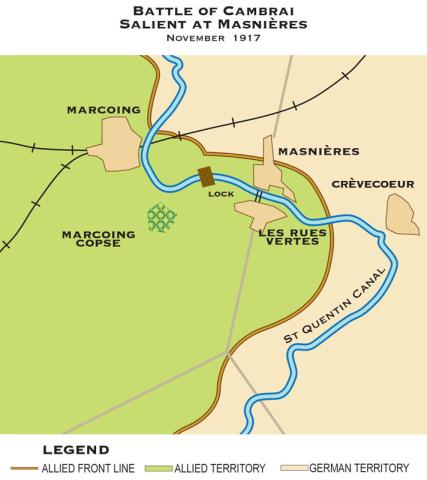

During this advance, the four tanks accompanying the 29th Division were disabled. However, the Newfoundland Regiment pushed ahead, clearing out small German garrisons hiding in the deep dugouts of the Hindenburg Support Line. The men continued their advance to the St. Quentin Canal, west of Masnières. There, the Regiment came under fire from the enemy's defences. With the support of another tank patrolling the area, the men captured the canal lock by approximately 1330.

The Essex, which had been assigned to advance on Masnières from the right, had not begun its attack because of delays earlier in the battle. Despite this, the Newfoundland Regiment attacked Masnières from the left, advancing along the banks of the canal. By sunset, troops had reached the edge of the village. During the night, small groups of men from the Regiment and other battalions worked in "mopping up parties" to clear Masnières of the enemy. By the next morning, all but a few patches of the village were in Allied hands.

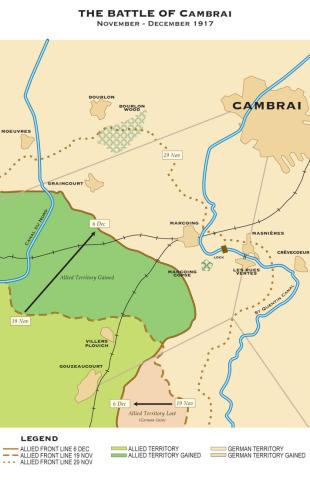

The Allies had managed to advance six kilometres during the first day of the battle. However, the territory they had claimed formed a salient.

Salient at Masnières

November 21

On November 21, the 29th Division was preparing to continue its offensive towards the Masnières-Beaurevoir Line. The Newfoundland Regiment was ordered to proceed to an abandoned sugar factory. On the way, a lone shell hit the marching men. It killed ten of them and wounded another fifteen. Among the dead were Provost Sergeant Walter Pitcher, one of the "Heroes of Monchy" (see Battle of Arras), and Lance-Corporal John Shiwak, an Inuk from Rigolet, Labrador.

Provost Sergeant Walter Pitcher

The Rooms Provincial Archives VA 36-38.1

Lance Corporal John Shiwak

The Rooms Provincial Archives A 11-147

The attack the 29th Division had been preparing for never materialized. It was determined that the troops were too tired to proceed and there were no reinforcements to replace casualties. The advance on Cambrai had slowed. In the fighting from November 20 to 21, fifty-four men from the Regiment were killed and another 184 wounded. The Allies were now on the defensive to keep the territory they had gained.

November 22 to November 29

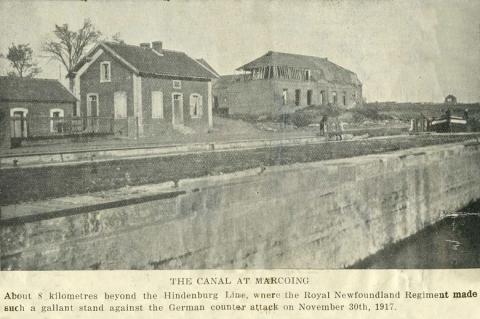

On November 22, the Newfoundland Regiment was put on reserve in the nearby town of Marcoing. Troops rested three days before proceeding to man trenches north of the canal. On November 29, the men returned to Marcoing.

Marcoing and Canal

The Rooms Provincial Archives

November 30 to December 3

On the morning of November 30, the Germans launched a counterattack. They bombarded Marcoing and attacked to the southeast of Masnières.

The Newfoundland Regiment was ordered to proceed to the front to help stop the German advance. The Regiment was surprised to find the enemy had advanced as far as Marcoing Copse. The men engaged in hand-to-hand combat to push enemy troops back, thus preventing them from cutting off the Allied forces holding Masnières. The day's fighting cost the Newfoundland Regiment fifty-seven men killed and seventy-four wounded.

For the next three days, the Newfoundland Regiment and other troops of the 29th Division were hit hard by shellfire. While the Allies held Marcoing, Masnières was evacuated on December 1. At 2100 on December 3, the men of the Newfoundland Regiment were relieved from the front line.

The Outcome

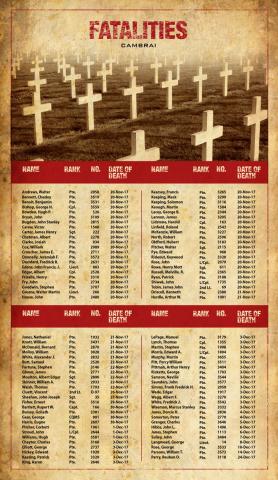

The Battle of Cambrai officially ended on December 7. The Allies had gained in some areas and lost in others. Overall, the Allies had gained little territory from the battle. British casualties numbered more than 40 000 while German casualties were estimated to be about 45 000. For the Newfoundland Regiment, casualties from the Battle of Cambrai numbered 352 wounded and 110 dead.

Territory Gained

Cambrai Fatalities

In recognition of its contribution at Cambrai and at the Third Battle of Ypres from July to November 1917 (sometimes referred to as the Battle of Passchendaele), King George V awarded the prefix "Royal" to the Regiment's title. This honour was not awarded to any other British Regiment during the First World War. Field Marshal Douglas Haig noted, "The story of the defence of Masnières and of the part which the Newfoundland Battalion played in it is one which, I trust, will never be forgotten on our side of the Atlantic."

The Rooms Provincial Archives

Sir Douglas Haig

The Rooms Provincial Archives E-2-16

War Diary: Masnières

PDF (250 KB)

The Veteran: Cambrai

PDF (3.8 MB)