A soldier's daily life was busy. From the morning reveille to the nighttime last post, a soldier had many tasks to which he had to attend. He would occasionally get leave when he could spend some time enjoying life in the area. Food and accommodation varied depending on what was available at that particular time. The Newfoundland soldier took matters in stride and made the most of his life in the British Army.

Not only a method of developing discipline, marching was often a means of simply getting from one place to another. Laden with heavy haversacks, and sometimes through the chill of night, it was not uncommon for men to cover fifteen kilometres in a single day. Whether on a rolling ship, in the baking deserts of Egypt, or on a frozen French field, marching helped keep the men in shape.

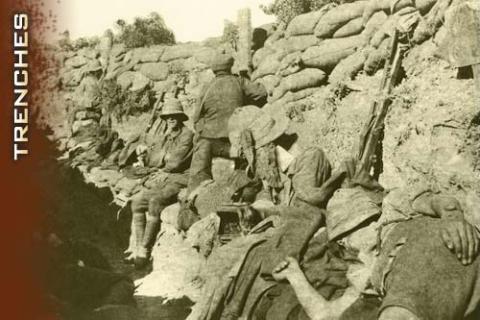

While only a fraction of a soldier's life was spent in front-line trenches, even a few days of damp, cold, muddy conditions were enough to bring on debilitating frostbite and trench foot. Adding to the misery, the noise of constant bombardment, a lack of proper beds, and the presence of vermin made sleep difficult at best.

Men Sewing in Trench

Memorial University of Newfoundland Archives and Special Collections Division

Medical - Soldiers could depend on a chain of medical care running from medics on the front lines to field hospitals, hospital ships, and military hospitals in the Mother Country. While at times there were allegations of preferential treatment for higher ranks, there was a general commitment of caring that spanned the decades to follow. Attention to the physical being through the provision of artificial eyes or limbs was taken seriously; however, psychiatric conditions like shell shock were as likely to be labeled cowardice or general weakness as given proper care.

Group of wounded Newfoundlanders, members of the 1st Newfoundland Regiment, at London‘s Wandsworth Hospital

The Rooms Provincial Archives VA 37-29.4

Accommodation - Much of a soldier's time was spent well behind the front lines billeted in barracks, private homes, stables, cellars, and sometimes even the enemy's former bunkers. Conditions were cramped and men were often accompanied by such numbers of rodents, lice, and mosquitoes that they preferred the aching cold of winter to the warmth of summer because it reduced the number of pests.

Food - Like most people in a foreign land, the men of the Newfoundland Regiment missed the comfort foods of home. Despite the occasional "liberated" veal or gift of wine, the fare most days was rather plain and sometimes cold. The fact that some men picked and ate vegetables as they crossed the battlefield says something about conditions. After the end of the war, dietary disappointments continued. While billeted at Hilden, Germany, the Regimental War Diary simply recorded for December 25, 1918 that "turkeys did not arrive."

Ladling out Rations

Centre for Newfoundland Studies Archives and Special Collections Division Coll 314-1-04

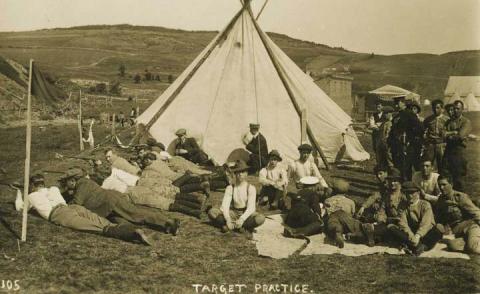

Training - From the shores of Quidi Vidi Lake in St. John's to as far away as Scotland and Egypt, the men of the Newfoundland Regiment received constant training. This included instruction in tactics, hand-to-hand combat, shooting, and the use of the newly developed gas mask. For some, in the weeks leading up to the Somme offensive, there was even a brief practice visit to the third line trenches.

Soldiers of the 1st Newfoundland Regiment at bayonet practice

The Rooms Provincial Archives VA 37-33.4

Target practice: Volunteers of the 1st Newfoundland Regiment, Pleasantville

The Rooms Provincial Archives VA-37-5-4

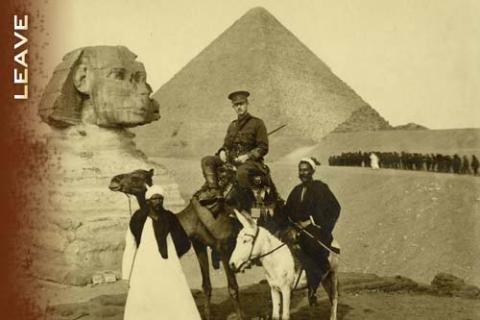

Within the limitations of rail passes and curfews, leave provided soldiers the opportunity to relax, socialize, and even do a little sightseeing. From the pyramids of Egypt to the wild coasts of Scotland, men sought out their own interests - many even meeting their future wives. However, for most of the First Five Hundred, nothing could improve on the special Blue Puttee Leave - granted in the summer of 1918 - which provided the opportunity to visit home.